This article looks at why the Covid-19 crisis is widening gender labor gaps and warns that, without the right incentives, the license for private workers with care responsibilities and the Telecommuting Law can deepen these inequalities.

Covid-19, economic autonomy and widening of gender gaps

The crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic is amplifying gender inequalities around economic autonomy through two channels.

On the one hand, because of what happens in the labor market. On average, women receive less income than men. This not only gives them less money to live from month to month but also reduces their chances of saving and supporting themselves financially if they lose their job. Likewise, women are overrepresented in sectors considered essential during Social, Preventive and Compulsory Isolation (ASPO) and in precarious jobs - that is, without labor rights or access to social protection, especially relevant in contexts such as the current one. They are also a very significant proportion in the sectors strongly affected by the crisis such as trade-in non-essential products, domestic work, social services and tourism.

Furthermore, despite their massive labor insertion over the last half-century, women continue to be the first to leave the job market and the last to return. Their role in care work explains a large part of this situation: social norms, public policies and institutions still respond to the traditionalist logic of women as caregivers and men as providers. Thus, female labor participation is considered a secondary or reserve source of income, which increases their chances of being unemployed. Unemployment in many cases expels them to inactivity due to a discouraging effect in the job search that leads them to hold an exclusive role in care.

The ASPO also showed that women are less likely to telework. According to CIPPEC estimates, men have a greater potential to perform at a distance (32% -34%) than women (24% -25%). This is explained by the characteristics of the jobs they perform: men are the majority in managerial positions, which are easier to perform remotely, while women are overrepresented in the world of services, which requires greater proximity. Furthermore, whether they can telework or not, the familiarization of care during confinement sharpened their feminization: women are still in charge of these tasks, which can further affect their productivity. In this way, it is clear that flexible work measures, if they lack a gender perspective, fail to promote a better work-family balance or greater co-responsibility.

At a time when the vast majority of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) encounter challenges in generating income and meeting their expenses, entrepreneurs led by women can also be in greater difficulty. These companies tend to start more out of necessity than opportunity, have less funds and last less time, phenomena that can be extreme in times when many companies face severe restrictions to operate. However, women are also making greater use of digital platforms to promote their companies, which could give them a boost in the height of e-commerce.

The second channel through which the pandemic amplifies gender labor inequalities is what occurs within households. Confinement measures linked to ASPO increase women's risk of suffering domestic violence. In mid-April, the number of complaints already showed an increase of 39% compared to the same period of the previous year.

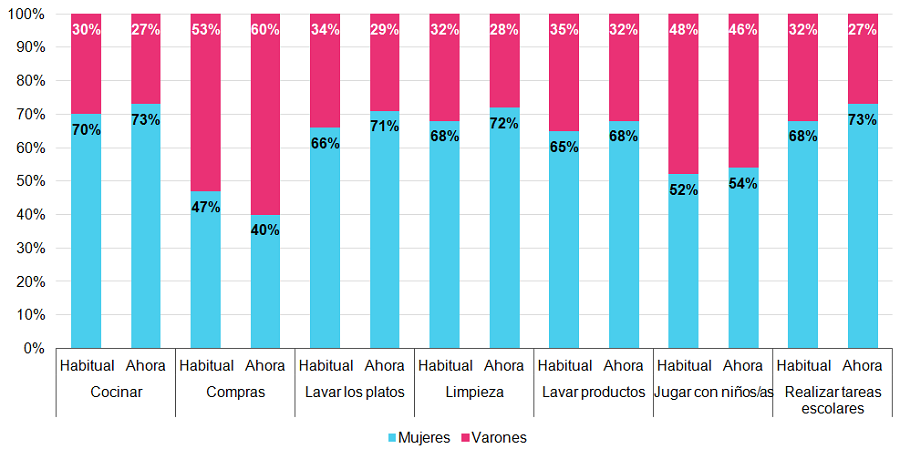

Likewise, the ASPO made it necessary to familiarize the care and deepen its feminization. The suspension of face-to-face classes, child-rearing, teaching and care services, and domestic work increased the unpaid work performed by women in their homes. According to data from April, women perform in a higher proportion than usual all domestic activities related to care and cleaning (UNICEF, 2020). The only exception is shopping outside the home, which has always had a more equitable distribution and now men do more frequently. This phenomenon reaffirms a clear trend: men occupy the public sphere while women are relegated to the home.

Carrying out household chores in families with a male head, by sex. Total country. April 2020.

In the diversity of families, it is single- mother households –composed of mother and children– who face the most difficulties. These households, which represent one in five in the lower-income sectors, have the head of the household as the sole responsible for the care and economic support of the family, which generates strong tensions between their work and personal life. In a context of less female labor participation and labor inclusion in precarious conditions, the loss of income and the uncertainty caused by the ASPO become a particularly difficult problem for these households.

Reduce inequalities to guarantee rights through public policies

The tensions between women's labor participation and their role in caregiving have been evident for decades and increase in periods of crisis such as the current one. In this framework, it is a priority to implement actions that contribute to closing pre-existing inequalities, especially around care work.

Recently, Congress and the National Executive Branch discussed two actions in order to facilitate the reconciliation between the productive and reproductive life of families.

On the one hand, the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security and the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity published a joint resolution that establishes a special license for households with care responsibilities during the remaining term of the ASPO and the suspension of classes. In households with children under 6 years of age, one of the parents will have the right to take leave from their tasks, while households with children from 6 to 12 years of age or with someone who cares for people with disabilities or people Elderly dependents may request the adaptation of the working hours to their responsibilities. Although the resolution mentions the need to promote joint responsibility between the genders, it leaves its implementation in the hands of the employers and workers.

On the other hand, the Chamber of Deputies approved a bill to create a legal regime for a telework contract, which would come into effect 90 days after the end of the ASPO. The project declares remote work as a work modality foreseen in the law and establishes various issues that affect their working conditions, such as working hours, rights and obligations and the allocation of expenses associated with work items and connectivity, among others. The novelty regarding gender issues is that people with responsibilities for caring for children under the age of thirteen, people with disabilities or older people “will have the right to schedules compatible with the care tasks they are responsible for and / or interrupt the day ”. The specificities of this right and others are left to collective bargaining.

The spirit that guides these two measures is, without a doubt, laudable: recognizing the burden that care work generates in households and the difficulties of reconciling it with paid tasks. However, without precise instrumentation, it is possible that both measures tend to widen the gaps they seek to reduce. On the one hand, the evidence is overwhelming. Regarding the cases in which the use of leave days is left to the discretion of the families or the employers: social norms prevail and the use ends up being feminized. On the other hand, the measures do not consider the diversity of needs that may arise from different formats of families, and in this way they can also widen inequalities (both gender and socioeconomic). The gender perspective needs to be more strongly incorporated to ensure that its effects actually promote greater equality. Cultural change can occur on its own, but it takes time: public policies have the potential to accelerate transformations to promote a greater role for men in caregiving and a better adaptation to the diversity of family formats, but they must thus explicitly implement it.

There are two types of homes that require special attention from care policies. On the one hand, families with children made up of two parents of different gender, since they are the ones that register a greater female overload of care work and actions are required to promote their redistribution. On the other hand, single-parent households (which are mostly single-parent), and which, as described, face severe difficulties in balancing care with income generation.

From the State, it is necessary to establish incentives for men to use care licenses and not to deepen the feminization of these tasks. Some of the mechanisms adopted in international experience to promote shared use are the granting of more days of license if use is made equally distributed or reserving a quota of days for the exclusive use of men.

In the Argentine case, the economic context may generate reluctance in some sectors to implement this type of measure (especially the extra days). Therefore, for people with care needs who have more than one person who can take care of their care, the actions of the State should aim to distribute the license equally among them. That is, when a child has both parents, they could divide the care license equally.

In the case of people with disabilities and older people, it is important, first of all, to differentiate from the population as a whole those people who actually present a certain degree of dependency or greater health risk. For them, the possibility of two or more adults dividing the leave period alternately could also be considered. In this way, the measure could become more sustainable, by spreading the cost of the leave among several employers.

Another option to consider is granting different salary replacement rates according to the gender distribution of licenses, as used in several European countries. In this way, households with two providers that do an equitable shared use, or in which the male takes more days of leave, could receive a higher replacement rate than those that perpetuate the feminization of care. In the case of monomarentals in which the other parent does not participate in raising the children, and therefore they do not have the possibility of sharing care, the replacement rate should be equivalent to that of households that make an equitable distribution.

For the regulation of telework, it is also necessary to encourage greater co-responsibility in care. Central to this is a better public-private articulation to incorporate incentives or quotas so that telework is used by father workers to the same extent as mother workers.

These actions must go hand in hand with a strong communication campaign that highlights the importance for women, men and society as a whole of promoting greater social co-responsibility in care.

To promote better public policies that promote gender equality, it is crucial to generate data and evidence. In this sense, when implementing care licenses, organizations must keep a record of the use of licenses and telework that are disaggregated by gender and take into account the number of dependents and their characteristics (if they are children, people with disabilities or older). It is essential that this information be disseminated and used to make decisions about the measures that can continue in the progressive economic reactivation.

The measures taken by the health and economic emergency cannot resign the progress made around gender equality by default. Building on the advances of recent days, the State must take an active role in ensuring that these measures contribute to the redistribution of care between women and men. The crucial role that care plays in life as we know it was made clear by the pandemic and opens an opportunity to review the social pacts around its organization. If we do not achieve this, the widening of inequalities can lead to a less sustainable economic reactivation than desired.